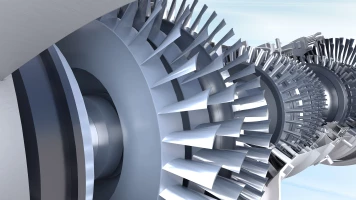

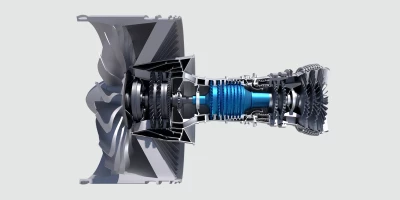

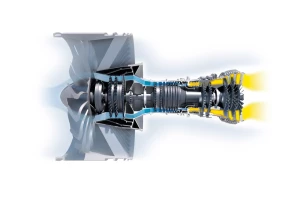

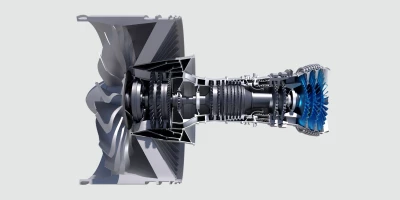

In 2015, things got really serious for “Set 1” when the first two ECM/PECM series production systems at MTU Aero Engines’ Munich site had to show what they could do. The electrochemical duo was tasked with manufacturing the compliance hardware for the PurePower® PW1100G-JM Geared Turbofan™, the engine for the A320neo: the fifth and the sixth high-pressure compressor stages. These are blisks with a diameter of around 450 millimeters and blades with extremely complicated geometries. The sample components were rigorously tested by client Pratt & Whitney with regard to strength and geometry—and they passed. Series production commenced in September 2015, and since then two further systems have come on stream; a third pair is under construction and another two are in planning.

MTU has been working on the cutting-edge PECM technology for some time now. This development was set in motion by the realization that the blisk design was gaining more and more acceptance—including growing popularity in the area of high-pressure compressors. Blisks have one major advantage over their counterparts with individually inserted blades: with integral components, the blade angle can be set such that the respective stage works more efficiently. As a result, the individual stages can each compress air more effectively. Thanks to the integral design, the edge load on the rotor disks is reduced, which saves weight. In addition, the elimination of leaks enhances the efficiency in the compressor. “Both these things together reduce fuel consumption—and therefore the engine’s CO2 emissions as well,” explains MTU engineer Thomas Frank, who heads rotor production operations and is responsible for nickel blisks.

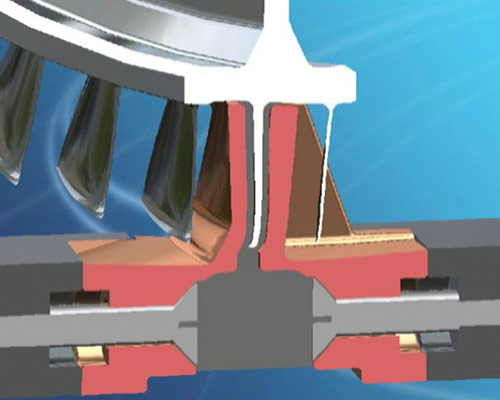

Precision work A finished high-pressure compressor blisk is removed from the machine. The component is already machined to net shape, because PECM is much more exact than conventional electrochemical ablation.

New method for new geometries and materials

From a technical point of view, however, the fuel consumption advantages and emissions reductions are not granted automatically. Temperatures of around 650 degrees Celsius prevail in stages 5 and 6 in the high-pressure compressor. Titanium is the material usually used to build compressors, but the lightweight metal ceases to have the requisite strength at these temperatures. For the PW1100G-JM, high-temperature-resistant nickel alloys are used instead, but these alloys cannot be processed cost effectively using conventional milling techniques because of the high level of tool wear. A further difficulty is the extremely complex 3D geometry of the blades, which stretches the ECM technique previously used with success for larger blisks to its limits. An even more precise method had to be developed—PECM.

As with the ECM method, PECM also involves using an electrolyte and electrical current to carefully and precisely dissolve a metallic material. The material to be processed acts as an anode (positive pole) and the three-dimensional, metallic tool acts as a cathode (negative pole). The big advantage PECM has over conventional machining techniques is that the tool does not touch the component, which means it does not incur process-related wear. An aqueous sodium nitrate solution is used as an electrolyte, which flows between the anode and cathode. This liquid has three functions: it establishes an electrically conductive connection; it carries away the removed material and the hydrogen created by the process; and it cools the process. Compared to the ECM technique, the PECM method achieves higher accuracies by employing extremely small working gaps in the micrometer range between workpiece and electrodes.

In contrast to conventional, single-axis processes, the workpiece is processed simultaneously with two electrodes which travel toward each other. This was not easy to master. Moreover, the electrolyte solution also had to be improved. Consequently, MTU decided to develop and build the mass production systems itself. “We’d already built up special know-how to the extent that we couldn’t find the same quality among external suppliers anymore,” explains Martin Bußmann, project manager for industrialization of the new method. “And, naturally enough, we also wanted to keep our edge in the knowledge we had acquired.”

MTU also plans to exploit the advantages of the PECM process for other components or manufacturing steps in the future. After all, in principle, the technique is suitable for many applications, such as for edge rounding or for manufacturing individual rotor blades and guide vanes. “The blade geometries for high-pressure compressors are becoming even more complex, and the materials are becoming ever more heat-resistant. This is pushing conventional machining technology more and more to the limits of its technical possibilities and cost effectiveness,” says production manager Frank. “PECM offers a future-proof alternative.”